Scientists have noted that during the past 50 years the weather around the world has become much more extreme. We hear from time to time of yet another natural disaster: a devastating hurricane in the Philippines, an unprecedented drought in Australia, severe floods in Europe, excessive forest fires due to prolonged heat waves and droughts in Canada, Greece and Hawaii, and snowfall in Cairo and Alexandria, Egypt, for the first time in a century. Every day the temperature hits new records: in Europe we experience exceptionally hot summers, and winter temperatures that plunge suddenly from above zero to -20°C.

Scientists refer to such freak weather conditions as weather anomalies. For example, unusually cold periods in the summer or a prolonged thaw during the winter are the most common weather anomalies in areas with temperate climates in the northern hemisphere. When weather anomalies pose a threat to the health, lives, and economic activity of people, they are extreme weather phenomena.

Figure 2.1.1 December rain instead of snow in Moscow is no longer a rarity

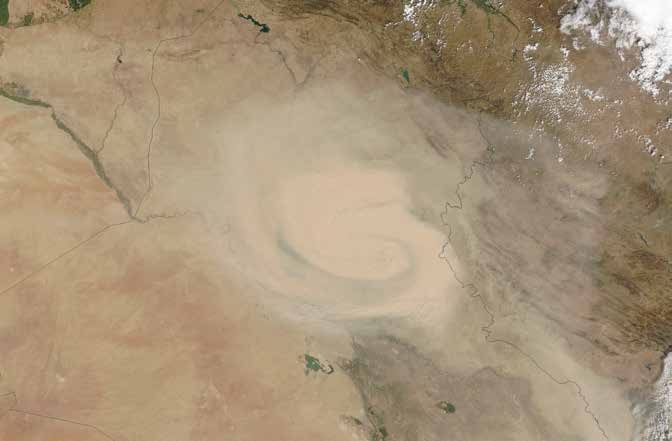

Severe sand and dust storms in the Middle East in 2022

Severe sand and dust storms are defined as storms caused by intense winds over areas of arid soil that pick up large amounts of ground material in the atmosphere. Approximately two tonnes of sand and dust enter the atmosphere each year, according to the United Nations Coalition to Combat Desertification. Sand and dust storms occur most frequently over deserts and regions with dry soil. In the Middle East and other arid regions, they can come in two forms. Haboobs (Arabic for ‘violent wind’) come from storm fronts and often appear as walls of sand and dust marching across the landscape. But like thunderstorms, haboobs don’t last long. Then there are the long-lived, wide-reaching dust storms that can last for days. In Iraq, such storms are often associated with the persistent north-westerly winds, called shamal (Arabic for North). The construction of more dams, mismanagement of water, extreme dryness, desertification, and other factors all contribute to this nightmarish phenomenon.

In April and June 2022, Iraq and other countries in the Persian Gulf were looking up at an apocalyptic orange sky with a flurry of sand and dust storms. There were reports of port, airport, road and school closures, and flight cancellations. The storm sent thousands of people to hospitals with breathing problems. Dust storms can be especially dangerous for people with asthma; besides, they can transport disease microbes. Dust storms also cause loss of soil, especially its nutrient-rich lightest particles, thereby reducing agricultural productivity.

In recent years, sand and dust storms have become more common in the Middle East and other arid parts of the world, such as North Africa, Northern China, Mongolia and Kazakhstan, Australia, as well as central United States. In Mauritania, where the Sahara Desert covers 90% of the territory, there were just two dust storms a year in the early 1960s, but there are about 80 a year today, according to experts at Oxford University.

Scientists say that more frequent dust storms result from poor farming practices, including overgrazing and ripping up the biological crust, as well as climate change and associated increases in global and local temperatures and droughts. It is now established that sand and dust storms are a global phenomenon that affect our economies, health, and environment, and not just in the drylands. This phenomenon impacts everyone – men, women, boys, and girls – but not all in the same way. The differences stem from gender-based roles in the productive, economic, family and social spheres. Furthermore, sand and dust storms can be life-threatening for individuals with adverse health conditions. They are directly related to land degradation and can be addressed through sustainable land management and by achieving land degradation neutrality.

Figure 2.1.2 Satellite image of a dust storm in Iraq on 7 and 9 April 2022

So, what is happening to the weather and what does climate change have to do with it?

Observations suggest that the number of odd weather patterns and extreme weather events is increasing steadily all around the world. Scientists believe that this may be linked with global climate change. As the average temperature on the planet rises, the evaporation of water from oceans, lakes and rivers increases. This in turn increases the amount of moisture in the atmosphere, which leads to heavy rain in some areas. Also, higher temperatures in the surface waters of oceans are causing highly dangerous tropical storms (typhoons) to occur much more often than they did in the middle of the last century.

As we would expect, climate change also leads to more frequent heat waves.

HEAT WAVE

is a period of at least five days, during which the average daily temperature is at least 5°C higher than what is normal for these days of the year.

A recent study published in Nature magazine says that heat extremes that previously occurred only once every 1,000 days are now experienced every 200–250 days. However, the effects of warming will vary around the world. Weather events at the equator will become more extreme, meaning poorer tropical countries with already frail infrastructure will experience more than 50 times as many extremely hot days and 2.5 times as many rainy ones. But some already dry regions including parts of the Mediterranean, North Africa, Chile, the Middle East, and Australia will have higher risks of droughts and freshwater shortages.

Another study in the same issue of the magazine concludes that we are now entering an era with heat extremes that simply would not have occurred without climate change. Using an event- attribution analysis that links actual events with climate change, it shows that the prolonged heat-wave conditions in both Siberia and Australia in 2020 would have been virtually impossible without climate change. The Siberian heat wave resulted in massive forest fires (releasing an estimated 56 million tonnes of CO2 into the atmosphere) and a collapse of infrastructure from the melting of permafrost, leading to the declaration of a state of emergency. A state of emergency was also declared for the Australian bushfires, associated with exceptional summer heat from late 2019 to February 2020, also known as the Black Summer.

Scientists who analysed the observed record highs in the southern hemisphere’s winter and spring in 2023 concluded that those temperatures were made 100 times more likely by climate change.

But it is important to remember that unusual weather is not equivalent to climate change. For example, a very cold winter does not necessarily mean that the climate has become cooler. Data must be collected over a long period (about ten years or more) before we can attribute changes to climate change.

Weather anomalies can cause huge damage to the world economy and lead to the loss of many human lives.

Examples of extreme weather phenomena in recent years

On 13 September 2023, torrential rains from Storm Daniel swept across several areas in eastern Libya. The port city of Derna was the hardest hit, with entire neighbourhoods swept away after two aging structures collapsed, creating a catastrophic situation. The International Organization for Migration office in Libya stated that at least 30,000 people were displaced, and the death toll quickly rose to at least 11,300.

A key reason for the high loss of lives was the lack of dam monitoring or evacuation orders despite Storm Daniel’s known path. The lack of state capacity to co-ordinate disaster relief efforts worsened the human impact.

The disaster in Libya comes after a string of deadly floods around the world in September 2023, from China to Brazil and Greece.

Tropical cyclones hitting underdeveloped and underprepared countries like Myanmar, Bangladesh, India, the Philippines, and Honduras have also seen very high death tolls in the past. Nations without the resources and political stability to adequately prepare for natural disasters bear damages with huge consequences for people and the economy.

Figure 2.1.3 The city of Derna, Libya on Wednesday, 13 September 2023. Floods from torrential rains killed thousands of people and washed entire neighbourhoods into the sea

Extreme weather events in Africa in 2023

While Libya’s floods in 2023 made global headlines because of the scale of the death toll, many other deadly extreme events in Africa failed to make international news. An analysis of all disaster data, humanitarian reports and local news stories by the research think tank, Carbon Brief, helped to create a more complete picture of the scale of extreme weather impacts in Africa in 2023 to date.

It shows that at least 15,700 people have been killed in extreme weather disasters in Africa in 2023 and 34 million have been affected by extremes:

- More than 3,000 people were killed in flash floods in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Rwanda in May. Scientists were unable to assess the role of climate change in the disaster because of a lack of functioning weather stations recording data in the

- At least 860 people were killed in floods and mudslides in February during Tropical Cyclone Freddy, the longest lasting cyclone on record affecting Madagascar, Mozambique, Mauritius, Malawi, Réunion and Zimbabwe.

- More than 29 million people continue to face unrelenting drought conditions across Ethiopia, Somalia, Kenya, Djibouti, Mauritania, and Niger.

- Countries in southern Africa have sweltered in a months-long winter heatwave, leaving many facing summer-like conditions for a continuous year.

Examining all recent extreme events and based on recent data, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration of the United States (NASA) confirmed that as Earth’s climate changes, it is bringing about extreme weather across the planet. Record-breaking heat waves on land and in the ocean, drenching rains, severe floods, years-long droughts, extreme wildfires, and widespread flooding during hurricanes are all becoming more frequent and more intense. NASA’s satellite missions, including the Earth System Observatory, provide vital data for monitoring and responding to extreme weather events, with explanations for each of them (Fig. 2.1.4).

Figure 2.1.4 The rotating graphic summarizes how climate change influences extreme weather across the planet, resulting in heat extremes, wildfires, droughts, tropical cyclones, heavy precipitation, floods, high-tide flooding, and marine heatwaves

Heat extremes: Since 1950, the frequency and intensity of heat extremes have increased primarily due to human emission of greenhouse gases. This includes high temperatures and dangerous heat waves. These events will become even more severe and common as the planet warms.

Wildfires: Hot, dry conditions raise the risk of wildfires. Acting as fuel, dry vegetation allows fires to keep burning once they start. As temperatures continue to raise globally, wildfires could become more frequent and intense in some regions, threatening lives and property.

Droughts: As the planet warms, some dry areas are getting drier. Warmer temperatures lead to greater evaporation of water from the surface, turning it into water vapour in the air. Since warmer air can hold more water vapour, this creates a cycle that leads to greater warming and even more evaporation. With less surface moisture, droughts of increasing frequency and severity occur.

Tropical cyclones: With a warmer ocean and more moisture in the air, tropical cyclones can produce more intense and sustained rainfall. Hurricanes, typhoons, and tropical cyclones are also raising coastal flood risk because rising seas lead to higher storm surges. Plus, the storms that form have a greater chance of rapidly intensifying.

Heavy precipitation: As the Earth’s temperature rises, the warmer atmosphere can hold more water vapor – providing more water for intense rainfall, snowfall, and other precipitation from storms. Heavy precipitation is already occurring more often and will become more frequent and intense with increasing global temperatures.

Floods: Increases in water vapour in the atmosphere mean some wet areas will get wetter. Extreme precipitation can exceed the capacity of natural and human-made drainage systems, leading to damaging floods. Rising sea levels will also worsen flooding near the coast.

High-tide flooding: As global temperatures increase, ocean warming, and the melting of land ice are causing sea levels to rise. This means high tides will become higher, leading to a greater risk of flooding even when it’s sunny. This is already occurring in some coastal cities like Miami and Bangkok.

Marine heat waves: Global warming can lead to extreme heat waves within the ocean. Corals and other marine life are not necessarily adapted to these higher temperatures and may die during multiple-day heat waves. Just like on land, marine heat waves are predicted to get more frequent and intense as the Earth warms.

Combined impacts: Many of these extreme weather events happen in combination with others. For some locations, heat waves and droughts are occurring together more often, a trend likely to continue as the planet warms. The same goes for flooding events, as heavy rainfall from storms and rising seas will increase potential damage along coastlines.

Can we predict extreme weather in advance?

Unfortunately, in most cases it is impossible to predict extreme weather phenomena. The maximum weather forecast range is up to 14 days, as the atmosphere changes completely every two weeks and air flows cannot be tracked for a longer period. For example, the most that can be said in advance is that ‘the winter will be 1°C cooler than usual on average’.

Short-term forecasts are more accurate. Weather forecasts for tomorrow, made by European meteorological services, are correct in 96% of cases, predictions for the day after tomorrow are right in 93% of cases, and 90% of three-day forecasts come true. At present long-term warning of severe weather events can be made only in general terms. For example, it can be predicted that the extremely high temperatures, which are now seen in northern Eurasia every 20 years, will occur three times more frequently (once every seven years) by the mid- 21st century, and probably every three to five years by the end of the century, making them almost a common phenomenon.

Should we put faith in weather lore?

Weather lore is folklore related to the prediction of the weather. Despite its popularity, it is of no help when it comes to weather forecasting. Even in the days of our grandfathers and grandmothers, traditional ways of predicting the weather often failed to work, and nowadays weather lore has completely lost its linkage to specific places where it might have been applicable. For example, the English have a saying, “Ash leaf before the oak, then we will have a summer soak; oak leaf before the ash, the summer comes without a splash.” This used to be true in certain parts of Britain. But people began to move around the country and abroad, taking the saying with them. The result has been confusion, and weather lore has lost any validity it might have had.

What are we to do? How can we deal with extreme weather events? Can we adapt to them?

The United Nations has recommended early warning systems as key elements of climate change adaptation and climate risk management, particularly for extreme weather events and sea level rise. Such systems can help communities living in coastal areas, along flood zones and reliant on agriculture, to deal with flooding and cyclones and thus reduce their vulnerability to extreme events. United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres has called for every person on the planet to be protected by early warning systems by 2027. He launched the Early Warnings for All Initiative (EW4All) in November 2022 at the Climate Change Conference (COP27) in Sharm El-Sheikh, Egypt. The United Nations also launched a partnership, Climate Risk and Early Warning Systems, to help high-risk countries with neglected warning systems in developing them. Similarly, WHO recommends early warning systems to prevent increases in heatwave-related morbidity and disease outbreaks.

Hurricane Irma in Antigua and Barbuda in 2017

There are several good practices in reducing the damage and devastating impacts of storms and hurricanes. In Barbuda, Hurricane Irma wreaked havoc in 2017, resulting in huge losses to property and the evacuation of all 2,000 inhabitants of the Caribbean Island to neighbouring Antigua. With financial assistance of of US$10 million from the global Adaptation Fund, Antigua and Barbuda have been implementing a climate change adaptation project since 2017. The project is designed to help the most vulnerable communities in the coastal McKinnon watershed to build resilience against flooding, hurricanes, and higher temperatures by adopting an integrated approach. Measures include restoring natural drainage canals and climate-proofing vulnerable homes and storm shelters to reduce flooding and disaster risks:

- Restoring natural drainage canals: by cleaning, widening and deepening drainage canals, retention ponds and culverts to natural sizes, this measure aims to build capacity to handle extreme rainfall and storms.

- Climate-proofing vulnerable homes: by providing access to an innovative, low- interest revolving loan programme, this measure helps vulnerable households to climate-proof their homes.

- Storm shelters to reduce flooding and disaster risks: by supporting community groups in depressed areas with grants, this measure sought to develop climate-resilient buildings to serve as storm The project also enhanced collaboration with other funds such as the Global Environment Facility’s Special Climate Change Fund by undertaking a hydrological study with their support and providing potential to scale it up.

In addition, you don’t need to be a scientist or a climatologist or even to work for the emergency services to answer the question of how to deal with extreme weather events. The answer is simple: you must start with yourself. You need to be observant, and you need to care. To be observant is a straightforward matter: keep up with the latest science news; don’t ignore calls to consider climate change when you work on long- term projects (for example, the construction of a new railway in a permafrost area should consider

In addition, you don’t need to be a scientist or a climatologist or even to work for the emergency services to answer the question of how to deal with extreme weather events. The answer is simple: you must start with yourself. You need to be observant, and you need to care. To be observant is a straightforward matter: keep up with the latest science news; don’t ignore calls to consider climate change when you work on long- term projects (for example, the construction of a new railway in a permafrost area should consider

the increased melting of permafrost). To be caring is a more complex task: we need to be more careful in our behaviour and change our habits – we need to learn how to save energy and how to behave in extreme weather situations. For example, it is useful to know how to provide first aid to somebody who has fainted from the heat.

How to keep safe in a hurricane, storm, whirlwind or tornado

When you hear a storm warning:

- close doors, windows, attic hatches and vents

- remove items that could be carried by the wind from windowsills, balconies and loggias

- turn off gas, water and electricity, extinguish fires in stoves and fireplaces

- prepare stocks of food and drinking water

- make sure you have all essential things and documents

- take shelter in a basement or a strongly built structure

If a hurricane, storm or tornado occurs without warning:

a) if you are at home:

- move away from the windows

- stay in your home and hide in a safe place (the basement or ground floor is best)

- take shelter in an underpass, shop or the porch of a building

- find natural shelter (a ravine, pit, ditch, etc.), go as far down as possible and lie flat on the ground

- stay away from billboards, bus stops, trees, bridge supports, power lines;

- do not in any circumstances touch electrical wires that have been torn loose by the wind

Do not leave your shelter immediately after the extreme weather has passed, as more strong winds could blow unexpectedly.

QUESTIONS

1

Is it harder to predict the weather for urban and rural areas? Why?

2

Imagine that your family wants to celebrate New Year out of doors. But what you do will depend on the weather: you might need to stay indoors if the weather is too bad. What is the earliest date when you will be able to predict the weather on December, at least roughly?

3

Why does extreme weather represent a danger to people?

4

Is an earthquake an extreme weather event?

5

Did the extreme weather events that we see nowadays (strong winds, floods, heat waves, etc.) also occur in the past?

6

What kind of adaptation measures are recommended to address the climate impacts of extreme weather?

TASKS

Find out from your geography teacher what the main features of climate are in your location.

What was last summer like: was it warmer or colder than usual?