About 40% of the world’s population lives within 100 kilometres of the coast. Many of the world’s largest cities, ports and tourist zones are located on or near seacoasts, which account for more than 70% of total world production.

Coastal areas are closely linked with regions far inland. Impacts on coastal zones seriously affect the economy and living conditions, even in places that are far away from them. Coastal zones are highly vulnerable to the effects of climate change. The main threats to them are from rising sea levels, more intense storms that cause flooding and shore erosion, and more frequent extreme weather events.

The rising level of the world ocean

The level of the world ocean has been rising steadily for over 100 years, mainly because of global climate change. It rose by 15-25 cm, an average of 1-2 mm per year, between 1901 and 2018. That may not seem like much, but it presents a real danger for countries where the land is not much above sea level (or even below it).

The IPCC says that the rise in the level of the world ocean since the middle of the 19th century has been faster than the average in the previous 2,000 years. Since 1901, sea levels have been rising at an increasing rate. The average rate of sea level rise was 15-25 cm, or 1-2 mm per year between 1901 and 2018, increasing to 4.62 mm per year for the decade 2013-2022.

Human-induced climate change is mainly behind the rise in sea levels, and is caused principally by:

- Thermal expansion of water: as temperatures increase, water expands and takes up more

- The melting of glaciers in Greenland and Antarctica, which swells water flows into the world ocean.

In forecasting climate change, scientists use sophisticated mathematical models, which take account of the variety of factors that lead to climate change. Of course, these models cannot predict precisely by how many centimetres sea levels will rise in the next 30, 50 or 100 years. Though they apply scenarios that say that compared with 1995-2014, the level of the world ocean will rise between 15 and 29 cm by 2050 and between 28 cm and 1.01 m by 2100. Over the next 2000 years, the level of the world ocean will rise by about two to three metres if warming is limited to 1.5°C and two to six metres if limited to 2°C.

The expected rise in sea level by the end of this century represents a serious threat to coastal zones, the people living there, coastal infrastructure and coastal ecosystems, particularly small coral islands and the low-lying Pacific coast of South-East Asia. The rise will be uneven and is expected to be much greater in the tropics, where the 22nd century could see rises of one to three metres, followed by an increase of five to 10 metres from current levels in the following century.

High population growth and urbanization in low-lying coastal zones will be the major driver of risks resulting from sea level rise in the coming decades. By 2030, 108–116 million people will be exposed to sea level rise in Africa (compared to 54 million in 2000), increasing to 190–245 million by 2060 (medium confidence). By 2050, more than a billion people located in low-lying cities and settlements will be at risk from coast-specific climate hazards.

The Netherlands prepare for a climate shock

The Netherlands are very low-lying. A large part of the land in this small but highly industrialized country was originally obtained by draining coastal regions.

The Dutch have been developing technologies for the removal of water from their swampy plains for many centuries. Innovative Dutch engineers have long foreseen the threat posed by rising sea levels and have improved the design of hydraulic structures, which can hold back the advance of the sea.

Figure 2.6.1 Windmills were used to pump water from lakes

Figure 2.6.2 Afsluitdijk in The Netherlands is the biggest dam in Europe

Will coastal regions be swallowed up by the sea?

Coastal plains will be flooded because of rising sea levels, coastlines will be gradually swallowed by the sea, and fresh water supplies to coastal areas may break down. These changes can be catastrophic for densely populated coastal countries like Bangladesh, Nigeria, and Indonesia. Several major cities the world over are at risk from rising sea levels, including Shanghai, Bangkok, Mumbai, Jakarta, Buenos Aires, Rio de Janeiro, Miami, and New Orleans.

A rise in sea levels by 1 m will flood up to 15% of arable land in Egypt and 14% of arable land in Bangladesh, forcing millions of people to resettle. Salt sea water may infiltrate coastal groundwater, which is the main source of fresh water in many parts of the world.

In China, forecasts suggest that even a sea-level rise of 0.5m will lead to the flooding of about 40,000 km2 of fertile plains. Low-lying plains and the lower reaches of major rivers such as Yellow River and Yangtze River will be particularly vulnerable. The average population density along such rivers is sometimes as high as 800 people per km2.

In many of the Small Island Developing States (SIDS), the land mass rises only a few dozen centimetres above sea level. They could be submerged by the rising ocean, and their inhabitants forced to seek refuge in other countries.

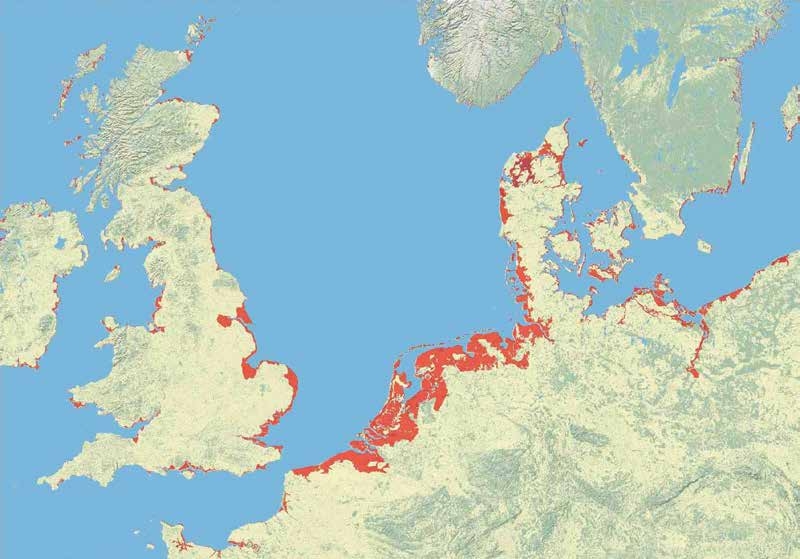

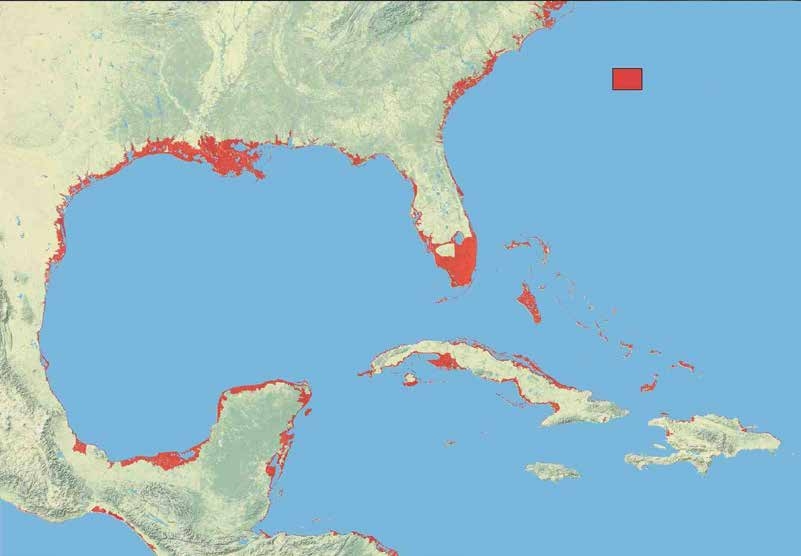

Figure 2.6.3 Forecasts of coastal flooding on different continents, assuming a rise of sea levels by 5 m

Storm warning

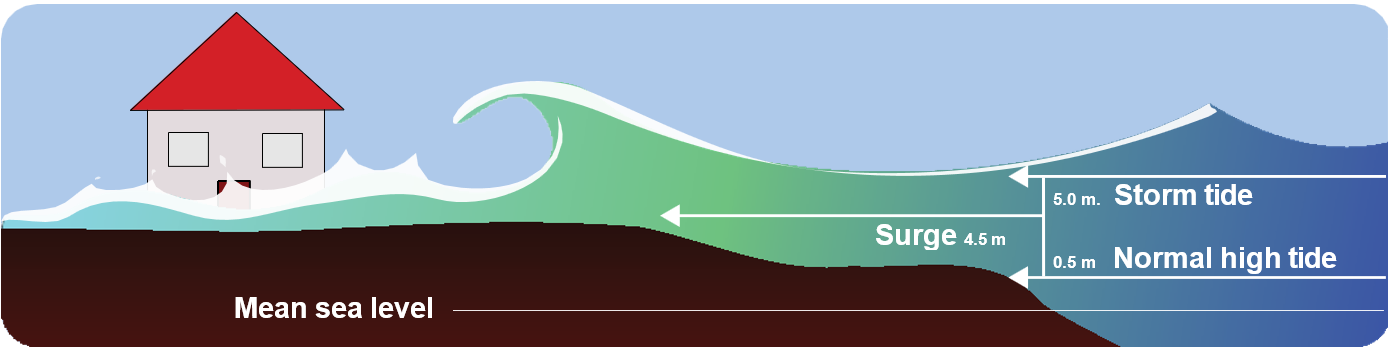

Storms have recently become more frequent in coastal areas and at sea. Extreme storm winds, whether near the coast or in the open sea, cause ‘storm surges’ – a sudden rise in water levels in water bodies that are semi-open to the sea (bays, the lower reaches of rivers). Storm surges attack coastal regions and are often accompanied by extreme precipitation and flooding, threatening the passage of ships, work on oil and gas platforms and seaside tourism, as well as causing coastal erosion.

Figure 2.6.4 Storms have become more frequent in coastal areas

Tragedy in the Philippines

In November 2013, the Philippines suffered a disaster comparable in scale to the tragedy in Japan two years earlier, when the latter country was hit by a giant tsunami wave caused by an undersea earthquake in the Pacific Ocean. The Philippines is an upland archipelago, which often bears the brunt of typhoons coming from the Pacific Ocean; as such, the Philippines effectively protects the Asian continent behind it. Such was the scenario in 2013.

In November 2013, the Philippines suffered a disaster comparable in scale to the tragedy in Japan two years earlier, when the latter country was hit by a giant tsunami wave caused by an undersea earthquake in the Pacific Ocean. The Philippines is an upland archipelago, which often bears the brunt of typhoons coming from the Pacific Ocean; as such, the Philippines effectively protects the Asian continent behind it. Such was the scenario in 2013.

First the Philippines was struck by a super typhoon Haiyan (known in the Philippines as Yolanda), which claimed 6,300 lives; and then it was hit by a second storm, Zoraida. Authorities said the disaster affected almost seven million people in the country (the freak weather destroyed 21,200 homes and damaged 20,000).

The catastrophic impact was from the storm surge reaching up to five metres – as high as two storeys – in some areas; and there was no dam to protect the coastline.

Figure 2.6.5 Storm surge effect

Erosion and destruction of coastline

Erosion and destruction of coastline by the sea is another consequence of rising sea levels (Fig. 2.6.6–2.6.9). Erosion is a particularly serious problem along the Arctic coastline, which was previously protected by ice, but is now losing ground rapidly as the ice cover has lessened and storm weather has become more frequent. The coast in the Arctic is retreating by as much as 10–25 metres or more each year in some places.

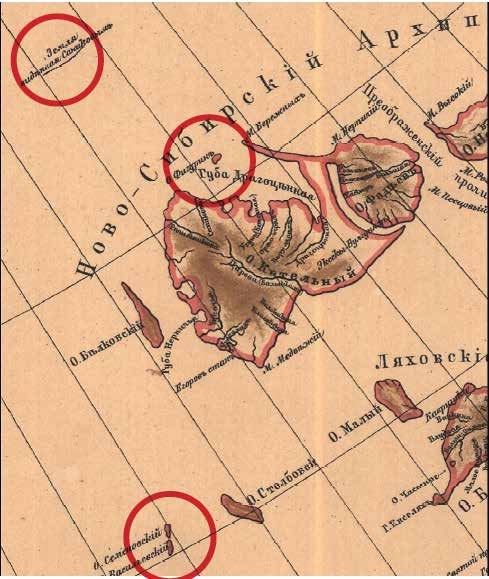

Figure 2.6.6 Destruction of coastline on the shores of the New Siberian Islands in the Arctic

Of course, the erosion of seacoasts by waves and floods is not something new. If you look at a map of island archipelagos from over 100 years ago, you will see that many islands in it no longer exist (Fig. 2.6.8). This process is now advancing more quickly. Light beacons that were originally built at a safe distance from the cliff-edge are falling into the sea (Fig. 2.6.9), large human settlements are being engulfed and their inhabitants must be resettled, and roads need to be diverted.

Figure 2.6.7 Example of eroded seacoast

Figure 2.6.8 Coastal erosion in the Arctic. On this section of a map from 1890 showing the Laptev Sea and the New Siberian Islands the red circles highlight islands that no longer exist (they were swallowed up by sea storms)

Figure 2.6.9 The Vankin coastal beacon (East Siberian Sea, Bolshoi-Lyakhovsky Island), which no longer exists

In Alaska, the entire village of Kivaluna, where 400 people lived on a narrow strip of land beside the Arctic Ocean, had to be abandoned and its inhabitants relocated away from the coastline. The cost of the operation was more than $200 million, although the village had no more than 70 dwellings.

Portugal’s disappearing beaches

Environmentalists are concerned by the impact of erosion on the coastline of Portugal, which could soon deprive this European country of many of its beaches.

In some places along the coast the sea is swallowing several metres of land each year, and the situation is critical in the northern region of Espinho, where the shoreline has receded by up to 70 metres in the last few decades. This process is irreversible.

Risk to coastal ecosystems

The rise in sea levels not only affects people and the economy but also sea and land ecosystems along the coast.

The ecosystems of coastal lowlands are particularly vulnerable since they are typically only a few centimetres above the sea. Such lowlands are the habitat of many species of animals and plants and play a key role in the accumulation of nutrients. These ecosystems include salt marshes, which are flooded with sea water at high tide. Mangrove forests, commonly found in coastal lowlands with a humid tropical climate, are also threatened by rising sea levels.

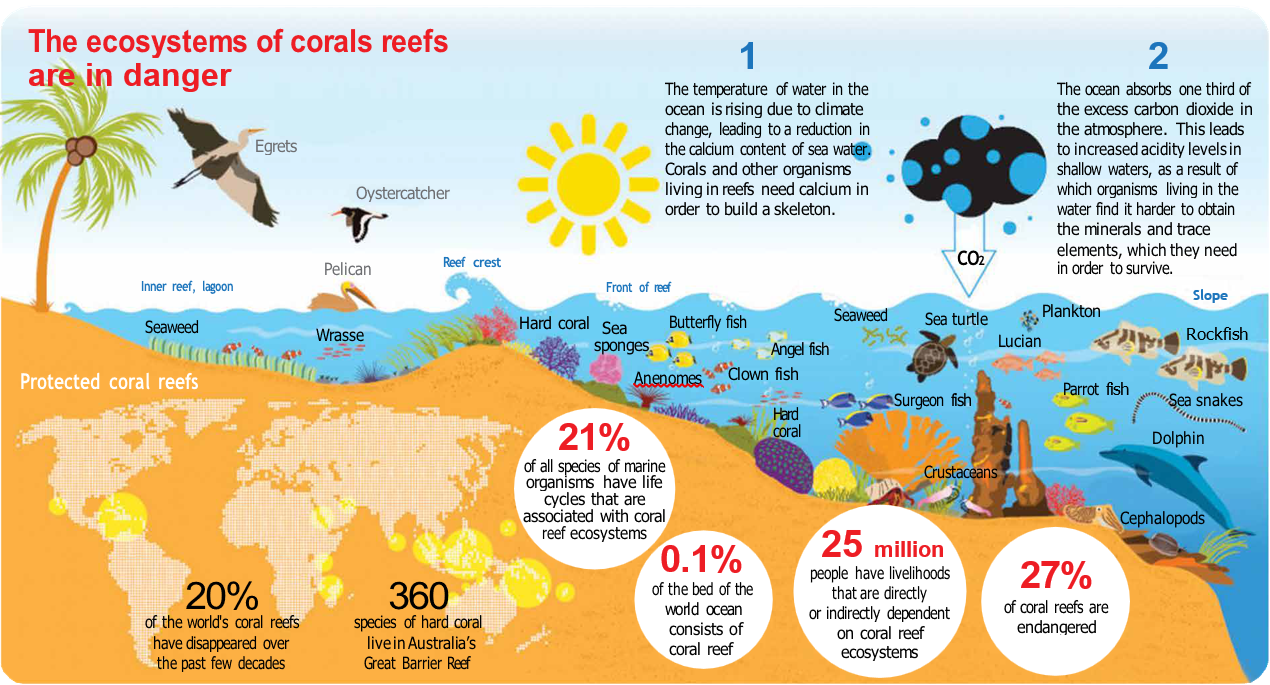

Global warming poses a significant threat to coral reefs since the rise in water temperatures above a certain limit will lead to bleaching of the coral. Bleaching means that corals lose the symbiotic algae normally found in their tissues and become white because of stress. If bleaching is severe or prolonged, they can die. Such coral bleaching is already being observed in many places.

Figure 2.6.10 Coral reef ecosystems at risk

A long-term increase in the temperature of sea water may lead to major degradation of the whole coral reef ecosystem. Coral atolls, which serve as a habitat for a great number of living organ- isms, may be destroyed. Forecasts by the IPCC suggest that 18% of the world’s coral reefs will be lost in the next three decades because of a variety of factors.

Climate change and fisheries

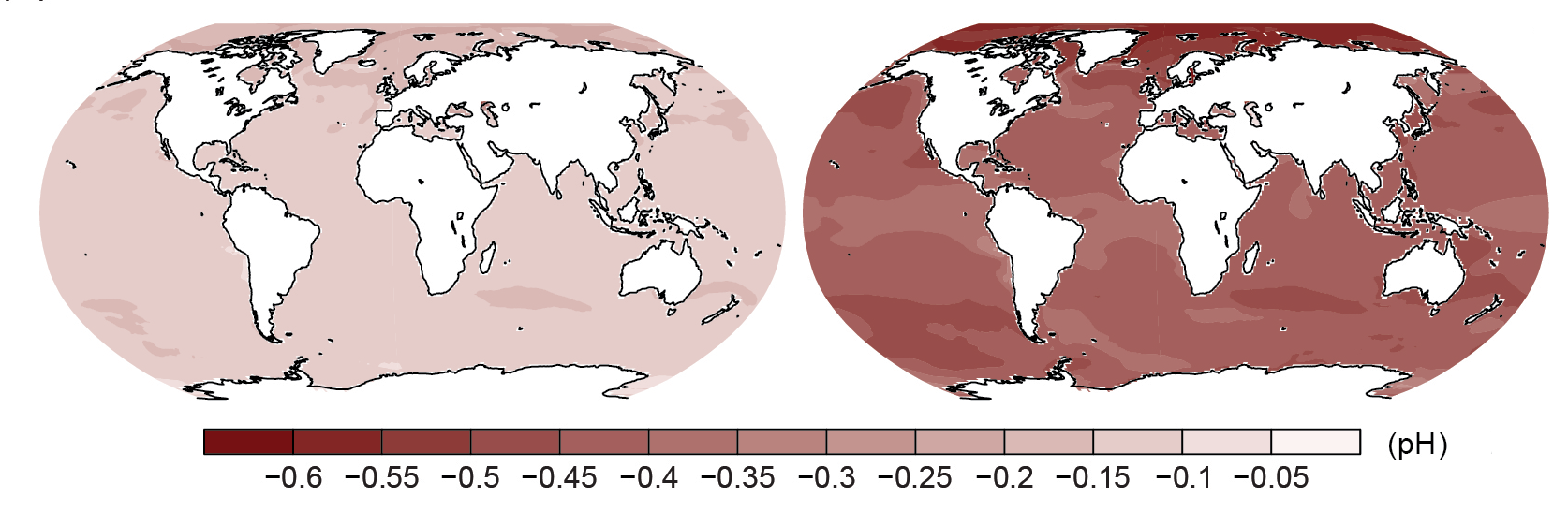

Scientists and fishermen are concerned by the increase in temperature and acidity of ocean water. As the concentration of CO2 increases in the atmosphere, its absorption by the ocean is also increasing, which raises levels of acidity (pH). Changes in pH and water temperature have been enough to cause coral bleaching. By the middle of the present century, acidity may increase by 0.06–0.34 pH, which is 100 times faster than the rate of change in the last 20 million years. Many marine organisms will find it hard to adapt to the new conditions, with serious impacts on fish diversity and productivity.

Figure 2.6.11 Forecast changes in acidity of the ocean’s surface water by the end of the 21st century under the most favourable (left) and the least favourable (right) climate change scenarios change

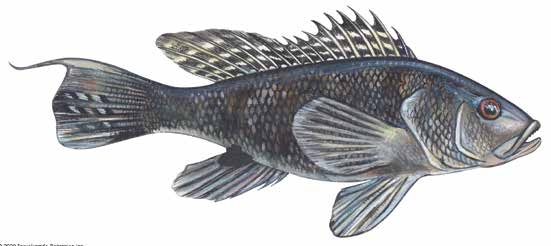

Figure 2.6.12 Black sea bass is moving North as the oceans warm

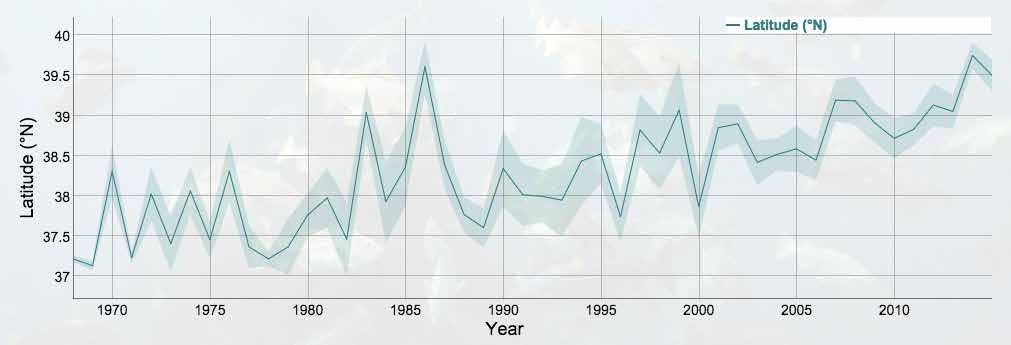

Changes in the properties of sea water are already leading to massive displacement of marine and freshwater fish species and the direction of their movements is not chaotic, but purposeful. Warm-water fish are moving to higher, cooler latitudes. This is not because of higher water temperature but a reduction in the amounts of phytoplankton, the staple diet of ocean fish, as the water temperature rises.

The numbers of cod off the coast of Greenland, and Japanese and Adriatic sardines increase during periods of climate warming and fall sharply during cold periods.

Many fish species are currently being fished at the limits of capacity to preserve their populations. Additional pressure from the need to adapt to climate change may push some species beyond their ability to reproduce in sufficient numbers to survive.

The loss of coastal habitats, including coral reefs and mangroves, is another major factor threatening fish populations.

The World Food Programme notes that fish represent more than 15% of the average protein intake for over 2.9 billion people. In small island states and some developing countries (Bangladesh, Cambodia, Equatorial Guinea, French Guiana, Gambia, Ghana, Indonesia, and Sierra Leone) fish provide more than 50% of animal protein intake. The populations of these countries are dependent on fisheries, so that any reduction in local catches represents a serious problem.

The rise in sea level is one of the changes to the global system resulting from climate change to which it is the most difficult to adapt. Strategies aimed at promoting adaptation are raising awareness of expected increases in the sea levels, improving early warning systems, and strengthening coastal defence and integrated coastal zone management.

QUESTIONS

1

Which country, Switzerland, or the Netherlands, will suffer the most if sea levels rise by more than half a metre?

2

Why are seacoasts being eroded rapidly?

3

What happened to lost islands?

4

Give examples of the impact of climate change on coastal ecosystems.

5

Why are some fish species moving to northerly latitudes?

6

What can be done to adapt to climate change in the coastal zones?

TASKS

1

Locate Tuvalu and the Republic of the Maldives on a physical map of the world. Find their height above sea level and explain why a rise in the level of the world ocean is so dangerous for them.

Find other island nations and coastal countries which are also in danger of being fully or partially submerged by the sea in the next 50-100 years. Suggest ways of addressing the problem.

2

Show on a contour map how the appearance of the continent of South America would change if sea levels rose by 100m.

Use coloured pencils to colour areas of land that would disappear under the sea. Think of geographical names for these areas. What will happen to the animals and plants there? Will they perish?

Write down your suggestions in an exercise book.

3

Using the OCEANADAPT webtoo (http://oceanadapt.rutgers. edu/), find out how different fish species in the USA have changed their habitats in the past 40–50 years. Which species had to move the most? Why are these movements happening?