What are mountains?

“What are men to rocks and mountains?” exclaimed Elizabeth Bennett, the heroine of Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice, excited about her forthcoming nature tour of pleasure in the summer. And it is true that mountains are one of the greatest creations of nature. What can compare with the breathtaking feeling when you stand on the top of a mountain, with only the blue sky above, and below you the world that looks so tiny, glimpsed under white clouds? At such moments you feel the beauty and power of nature, and at the same time its fragility.

Scientists define mountains as an elevated form of relief that rises above the surrounding plain. Unless they are volcanoes, mountains rarely stand alone, but usually form mountain ranges and ridges. Mountain ranges, in turn, come together to make mountainous countries or mountain systems.

Mountains may be high (above 3,000 m), of medium height (1,000–3,000 m) and low (up to 1,000 m). Low mountains usually have rounded summits and gentle slopes, but high mountains have steep slopes and angular peaks.

Mountains and climate

Mountains play a critical role in shaping the climate. They create a barrier to air masses, which cannot easily pass the high peaks. For this reason, different slopes of the same mountains often have different climate conditions, with more precipitation on one side than on the other. Average temperatures and landscapes may also differ significantly.

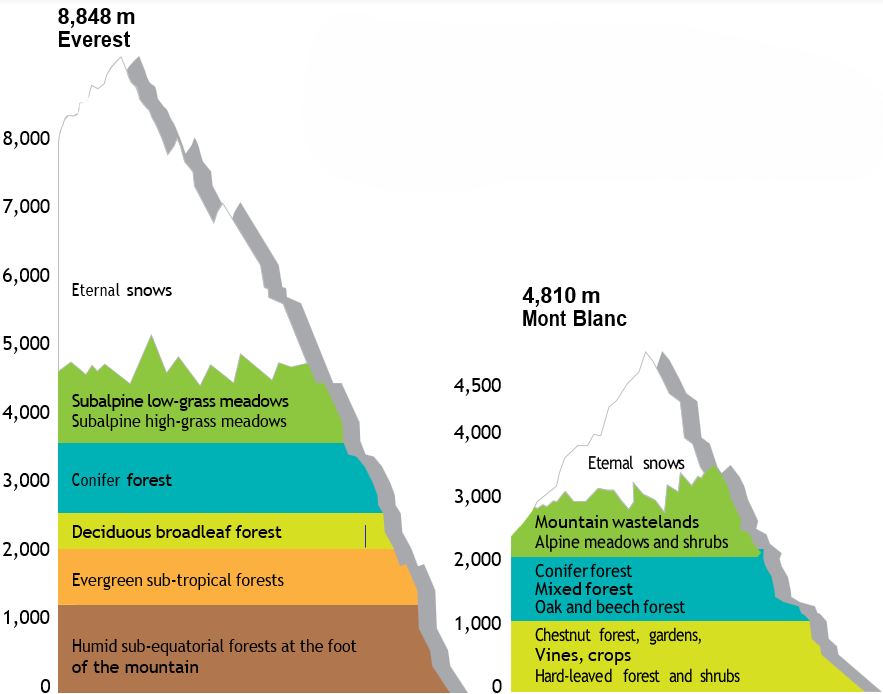

Mountains are also distinctive in that they bring together several different climates in a small area: the climate and landscapes change at different levels from the bottom to the top of the mountain. (Fig. 2.7.1). They are therefore called ‘altitudinal zones’ (‘altitude’ means ‘height’).

Figure 2.7.1 Altitudinal zones: Mount Everest (the Himalayas) and Mont Blanc (the Alps)

The world’s highest mountains

The highest mountain range on the earth is the Himalayas, which in Sanskrit means dwelling of the snows. Ten of the world’s 12 mountains that are over 8,000 metres high are located here, including the highest land point: Mount Everest, also known in local languages as Chomolungma or Sagarmatha. Mount Everest is 8,848 metres high.

The longest mountain range on land is the Andes. This gigantic South American mountain range extends along the entire Pacific coast of the continent.

Mount Aconcagua (6,960 m) in the Andes is the highest point in the western and southern hemispheres.

The largest mountain system in Europe is the Alps, which are shared between eight countries: Austria, Germany, Italy, Liechtenstein, Monaco, Slovenia, France, and Switzerland. Mont Blanc (4,807 m) in the Alps, on the border between France and Italy, is the highest point in Western Europe. The highest mountain on the European continent is the two-headed Elbrus Volcano (5,642 m) in the Greater Caucasus, which is also the highest peak of Russia.

North America has a system of mountain ranges, the highest of which are the Alaska Ridge and the Rocky Mountains. Mount McKinley (6,193 m) in Alaska is the highest peak in North America. Former US President Barack Obama announced on 31 August 2015 that Mount McKinley will be renamed Denali, as Alaskan natives call it. Africa’s highest mountain is Mount Kilimanjaro (5,895 m). The highest mountain in Australia is Mount Kosciuszko (2,228 m).

Figure 2.7.2 N. Roerich. Himalayas. Everest. 1938

Figure 2.7.3 The two-headed Elbrus volcano (5,642m), the highest peak in Europe

You’ve probably wondered why mountain peaks are often covered with snow, even in tropical latitudes. The first mountain climbers quickly found that the higher they went, the lower the temperature became and the harder it was to breathe. Air is heated by the sun and by the earth’s surface. Once it has become warm, it rises and expands, losing its heat. So, with increasing altitude, the air pressure, and its temperature gradually decrease.

With elevation, temperature falls on average by 6°C per kilometre from the earth’s surface. So, if the temperature at the foot of a 4,000-metre mountain is +24°C, the temperature at the top will be around 0°C. That is why, even though the average air temperature in the tropics never drops below zero, there can still be snow at high altitude on mountains.

Mountains affect the climate, but they are also highly dependent on it. Mountain regions are among the first to respond to changes in climate conditions. The main ‘indicator’ of climate change in the mountains are glaciers, which shrink or grow depending on whether the climate is becoming warmer or colder.

Melting beauty

Glaciers are formed in mountain ranges when the build-up of snow in the upper parts of the mountains turns to ice. The formation of a glacier requires a cold and wet climate, in which more snow falls during the year than has time to melt. As soon as temperatures rise and precipitation declines, the glacier ceases to grow and starts to melt.

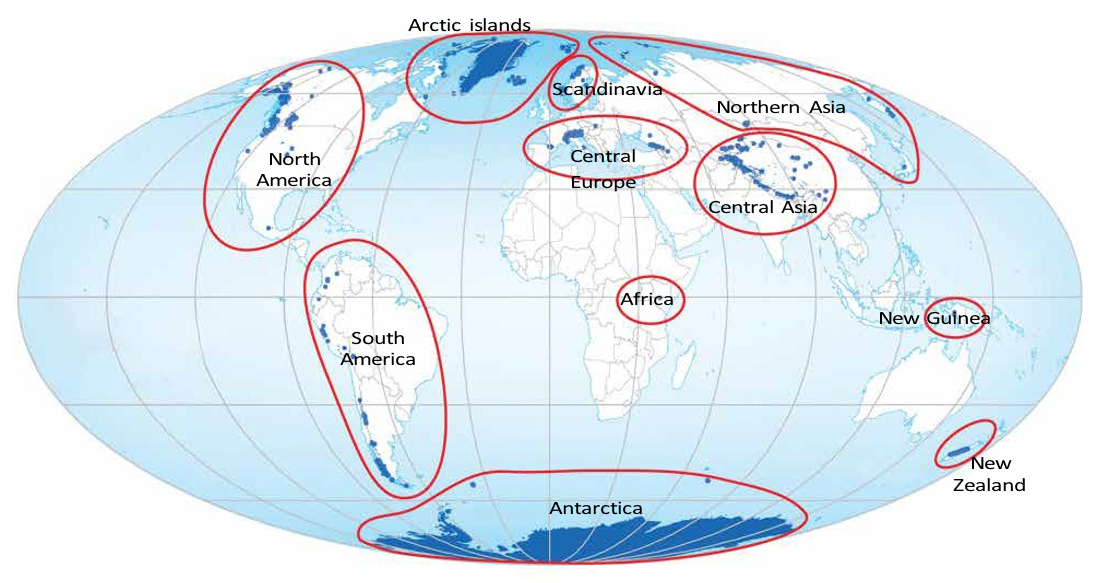

Figure 2.7.4 Glacial regions of the Earth

Mountain glaciers around the world began to melt (to ‘retreat’) about 15,000 years ago, when the last period of glaciation gave way to a new period of warmer climate. This melting process was accompanied by short periods when glaciers advanced once again. We know from history that in the 5th–7th centuries A.D., many mountain passes now occupied by glaciers were used as caravan routes. When the climate grew colder, glaciers began to grow, and by the 17th–18th centuries these passes were no longer open.

One example is the famous St. Gotthard Pass in the Alps. As the poet Frederick Schiller described it in 1799, “To the solemn abyss leads the terrible path / The life and death winding dizzy between,” crossing the snow-covered pass was wildly dangerous and possible only during a couple of summer months.

Figure 2.7.5 W. Rothe. Crossing St. Gotthard Pass, 1790

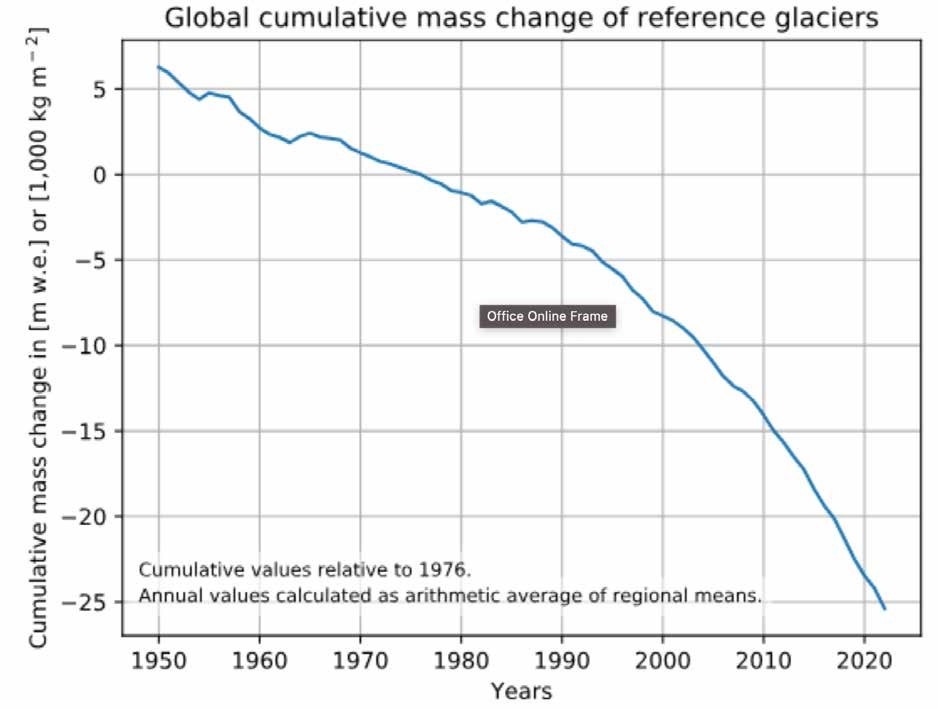

However, over the past 70 years, glaciers around the world have been retreating particularly fast (Fig. 2.7.6). Scientists are sounding the alarm: the rapid melting of mountain glaciers we are seeing today does not coincide with a natural cycle. A reduction in the volume of mountain ice may lead to catastrophic consequences for the environment and the economy of mountain regions, as well as their surrounding plains, which are home to as many as one in six of the world’s population.

Figure 2.7.6 Change in the mass of mountain glaciers around the world, 1950–2022, measured in units of meter water equivalent (m. w. e.)

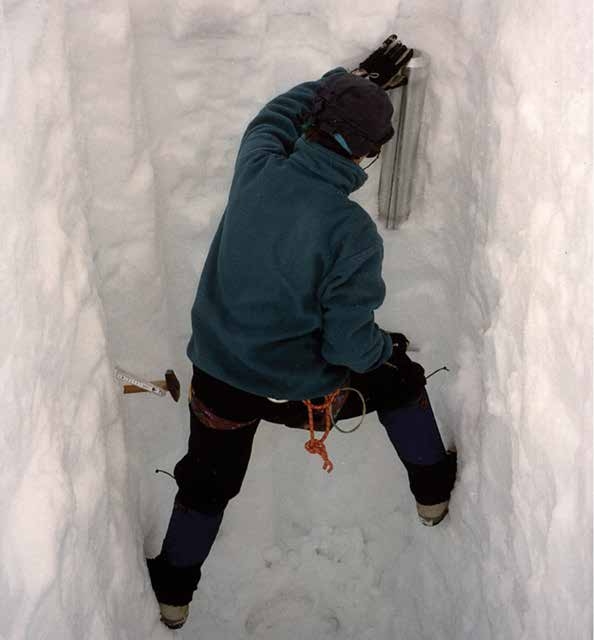

Figure 2.7.7 This is how scientists study glaciers

Mountain glaciers are retreating

Glaciers in the Himalayas are retreating by an average of 10–15 metres per year. The Gangotri Glacier, which is the source of the River Ganges, is melting particularly fast, retreating by 30 metres each year. Gangotri is one of the main sources of water for the 500 million people who live along the River Ganges.

Glaciers in Peru are also retreating rapidly. According to the most conservative estimates, their area has fallen by a third over the past 30 years.

The African volcano, Kilimanjaro, has suffered perhaps the worst of all: its famous ice cap, immortalized in Ernest Hemingway’s novel, The Snows of Kilimanjaro, has almost entirely disappeared.

Figure 2.7.8 The Gangotri Glacier

Figure 2.7.9 The cap of ice and snow of Mount Kilimanjaro has almost disappeared

Glaciers in the Alps are melting faster than ever. According to research conducted in 2023 by the scientific group Glacier Monitoring Switzerland (GLAMOS), Switzerland’s glaciers lost as much ice in two years as in the three decades before 1990: in just two hot summers in 2022 and 2023, the Alpine glaciers have lost the same volume of snow as that between 1960 and 1990. Scientists concluded that climate breakdown caused by the burning of fossil fuels is the cause of unusually hot summers and winters with very low snow volume, which have accelerated the melting of the glaciers. The European Environment Agency expects that 75% of Alpine glaciers will have melted by 2050.

In the mid-19th century, the Glacier National Park in the Rocky Mountains, on the border between USA and Canada, was home to as many as 150 glaciers. By the start of the 21st century, only 25 remained, and scientists predict that they will disappear in the coming decades, so visitors who want to see what the park was originally famous for should hurry up!

Figure 2.7.10 Glacier National Park in August 2013

The volume of glaciers in New Zealand decreased by 11% from 1975 to 2005. The most rapidly melting glaciers in that island country are the Tasman, Classen, Mueller and Maud glaciers.

Figure 2.7.11 The Greater Azau Glacier in the Caucasus. The photograph displayed by the woman is from 1956. Behind her you can see what remained of the glacier in 2007

The Azau glacier in the Caucasus has undergone significant changes. At the end of the 19th century the melting process caused it to divide into two parts, called the Lesser and Greater Azau. Today the Greater Azau is no longer great. From 1957 to 1976, the glacier retreated by 360 metres, and then by a further 260 metres from 1980 to 1992. The Lesser Azau retreats by about 16 metres each year.

The number of glaciers in the Altai Mountains in Eastern Russia decreased by 7.5% from 1952 to 1998, and those which remain have retreated by 100–120 metres from their position in the mid-19th century. The Sofia glacier, being observed by experts from Altai State University, has retreated by 1.5–2 km in the last 150 years. This glacier is also ‘rising’ at a rate of 20–30 metres each year.

How climate change affects people who live in the mountains

Living in the mountains is not easy. The high altitude, difficult terrain and frequently changing weather make it much harder to grow food and manage cattle here than on the plains.

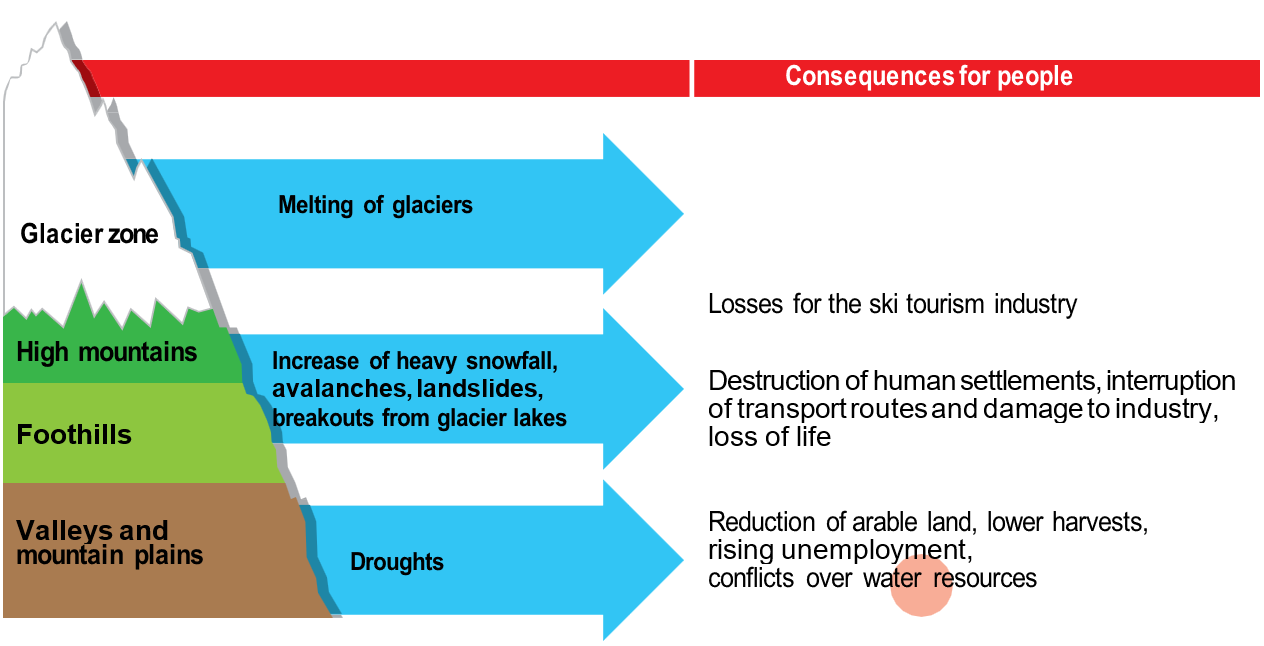

Figure 2.7.12 The impact of climate change on human life in the mountains

Since ancient times, people have settled in narrow mountain valleys, separated from one another by high mountain ranges with steep slopes, which often made contact between the neighbouring valleys (and populations) difficult. Even now, people living in mountainous regions often have their own unique customs, culture, and ways of making a living. The way of life of mountain people and their principal livelihoods – agriculture and tourism – are directly dependent on the climate. Even small changes in climate can affect their wellbeing.

Tourism going downhill

The example of the Alps shows how climate change is affecting tourist industry in mountain areas. Ski tourism provides up to 20% of the income of Alpine countries (Fig. 2.7.13). For the 13 million people living in the Alps in Austria, Germany, Switzerland and France, the lack of snow is an economic catastrophe: two thirds of all tourists who come here do so for skiing and snowboarding.

Forecasts give serious cause for concern: by 2030 there will be almost no snowfall in the Alps below 1,000m altitude, which will put many popular ski resorts out of business. Half of all the ski resorts in Austria are at altitudes up to 1,300 metres and will be forced to close due to lack of snow. The pessimistic predictions are already starting to come true: in the winter of 2006–2007, as many as 60 of the total 660 alpine ski resorts remained closed, and many others could only operate by using artificial snow, which greatly increased their already high costs. The result has been a fall in demand for holidays in the Alps.

How can mountain regions cope without snow? The sport and leisure industry is adapting as best it can, working to develop other types of tourism and recreation, which are less dependent on snow. Areas that were used for skiing are being converted into leisure parks and all-year-round health resorts. A time may come when people will go to the Alps, not for winter sports, but to enjoy walks along mountain lakes, savour the local food and breathe the fresh mountain air.

Figure 2.7.13 Tourist industry makes a large share of the income of mountain regions

Figure 2.7.14 Bridge over Trift Lake, Switzerland

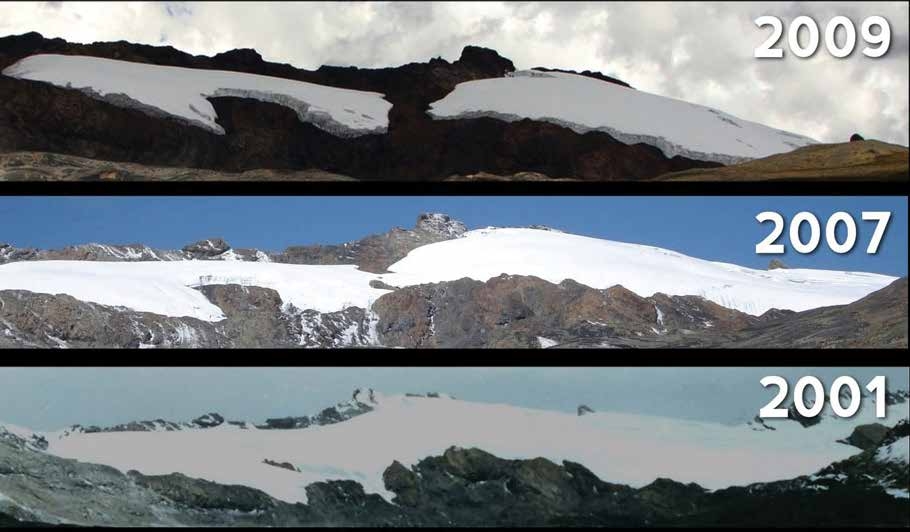

The Pastoruri Glacier in Peru is retreating

Until recently, tourists and professional climbers used to flock to the Pastoruri Glacier, which towers over the Andes in Peru. But the glacier has shrunk by more than a quarter in the last 35 years and scientists predict that it may disappear altogether in the next few decades. A breathtaking landscape of snow and ice has given way to black cliffs. Local authorities have prohibited climbing because the melting glacier has made the rocks unstable.

The number of tourists who come to admire the Pastoruri Glacier has fallen three times since the beginning of the 1990s, with major impacts on tourism in Peru and the income of residents. But Peruvian entrepreneurs have not despaired: they now show off the remains of the glacier as a striking example of the results of climate change, and the region has been successful in attracting increasing numbers of environmentalists and curious tourists.

But, of course, restoring the glacier itself is a much harder task than restoring the fortunes of local business.

Figure 2.7.15 Retreat of the Pastoruri Glacier in the Peruvian Andes

Natural disasters in the mountains

The decline of the tourist business is not the deadliest threat to mountain people from global warming. They also must fear natural disasters – avalanches, landslides, and floods – which have become ever more frequent in the mountains as the climate changes, posing a threat to human life and causing huge damage to the local economy.

When a glacier retreats it produces melt water, which accumulates in a mountain valley to form a glacial lake. As the quantity of water increases, the lake may overflow, causing a flood. Scientists believe that 20 glacial lakes in Nepal and 24 in Bhutan pose a serious threat to people living further down the valley. If these lakes breach their banks, and the water gushes into the valley, many people are in danger of losing their lives and/or their homes. Several such floods have already occurred in recent years in the valleys of the Thimphu, Paro and Punakha-Vangdu rivers in Bhutan.

The danger to the local population can be reduced by digging protective channels and dams before such flooding occurs.

Figure 2.7.16 Glacial lakes in the Himalayas

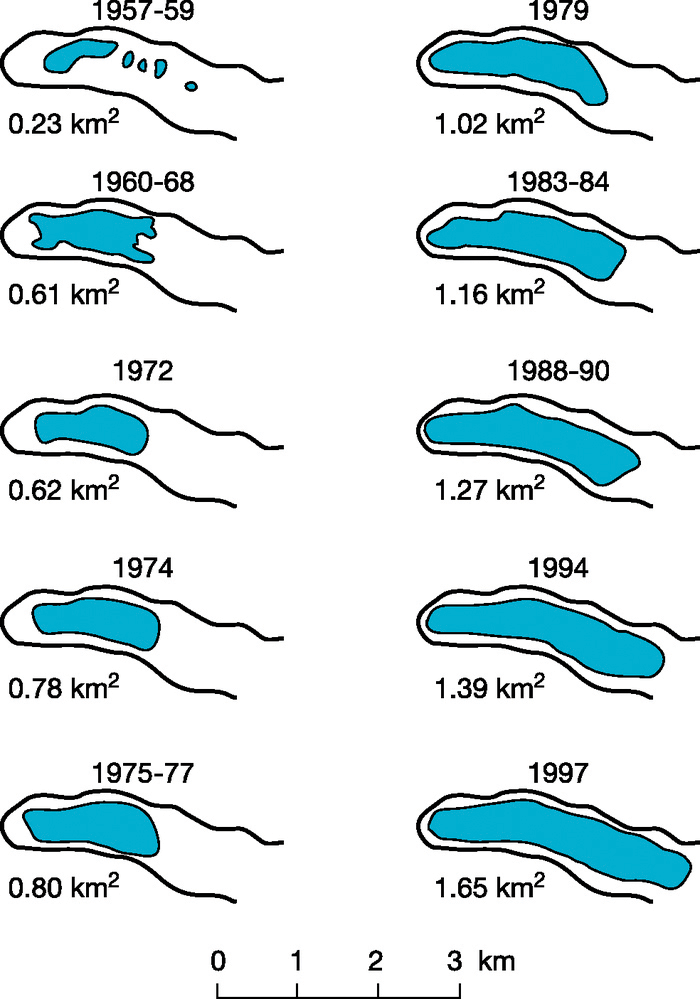

Figure 2.7.17 Lake Tsho Rolpa has grown by seven times in the past 50 years

Reduction of freshwater stocks

The future reduction of freshwater stocks, both in mountain regions and in adjacent plains, presents a serious threat. Glaciers are one of the main sources of fresh water since they are the source of many rivers. Melting ice will lead to water shortages in the regions around mountains, making conditions much worse for agriculture, mining, and electric power generation. A shortage of fresh water in areas near mountains is already leading to serious political conflicts in some parts of the world. Scientists note that climate change impacts on the mountains, such as hydrological changes resulting from the retreat of glaciers or some ecosystem changes, cannot be reduced through adaptation measures.

Mountains have always been associated with danger, and climate change may add to the risks. Rise of temperatures, changes in the amount of precipitation, the melting of mountain glaciers, and the more frequent occurrence of unpredictable natural disasters could lead to catastrophic consequences for the environment, the people and the economy of mountain regions and surrounding areas.

QUESTIONS

1

How high has a mountain climber climbed if he is at a level where the tem- perature is -9°C, when the temperature at the foot of the mountain is +18°C?

2

Will snow remain at the top of a mountain 5200 m high, if the air temperature at its foot is +30°C on the hottest day of summer?

3

Why are mountain glaciers often called indicators of climate change? What happens to them when the air temperature changes?

4

Why is there often a great deal of ethnic diversity in mountain regions?

5

What are the main livelihoods of people living in mountain regions? How are they affected by climate change?

6

What can be done to preserve the main livelihoods of people living in the mountain regions and adapt to consequences of climate change?

TASKS

1

Mark the highest peaks on each continent on a contour map of the world. Which mountain systems are they a part of?

In which countries are they located?

2

The beauty and the inaccessibility of mountains have always inspired the greatest poets, writers, artists, and composers. Name some famous works of literature or art that show various mountain ranges or peaks. Choose any work that you particularly like and explain what the author would have to change if they had lived in an era of global climate change. How could they do it?